NEWMAN AND VATICAN II

How do we best understand Saint John Henry Cardinal Newman as “the Father of Vatican II?”

The July 22, 2009 L’Osservatore Romano article cited below offers a concise if somewhat dense summary of Newman’s specific doctrinal contributions to and influence on Vatican II teachings and developments.

begin

His Scriptural and Patristic theology was alien to a Church that was then dominated by a scholastic theology and untouched by the later Scriptural, Patristic, and Thomist revivals. It was the Second Vatican Council, of which he is often called “the Father”, that finally vindicated his theology. The late Cardinal Avery Dulles called him the most seminal Catholic theologian of the 19th century. His classic Essay on the Development of Christian Doctrine (1845), which fell under the suspicion of the two leading Roman theologians of the day, is the starting-point for modern Catholic theology of development. His On Consulting the Faithful in Matters of Doctrine (1859), which was denounced to Rome by one of the English and Welsh hierarchy, predated by more than a hundred years the Second Vatican Council’s Decree on the Apostolate of the Laity and the chapter on the laity in the Constitution on the Church. The final chapter of the latter on the Blessed Virgin Mary was the result of the Council’s decision not to have a separate document on Our Lady; its Scriptural and Patristic theology is in accord with Newman’s own Mariology in his A Letter to Pusey (1866). Newman’s interpretation of the First Vatican Council’s definition of papal infallibility in his Letter to the Duke of Norfolk (1875) was unwelcome to the extreme Ultramontanes but was vindicated in his own time in True and False Infallibility by Bishop Fessler, who had been Secretary-General of the Council, a book that received the official approval of Pope Pius IX. Newman’s famous “toast” to conscience in the same work referred to the possibility of conscientiously refusing to obey a papal order, not to the possibility of so-called conscientious dissent from papal teachings, as is often falsely alleged.

But if Newman is “the Father of the Second Vatican Council”, he will, in the event of his canonisation, surely be declared a Doctor of the Church. And if so, he will be seen, I am convinced, as the Doctor of the post-conciliar Church. For his theology, that seemed so radical, even dangerous in his own time, was always deeply historical and sensitive to the Tradition, as well as respectful of the teaching authority of the Church. He once famously wrote, “To be deep in history is to cease to be a Protestant”. The idea that Vatican II represented a complete break in the history of the Church, a new dawn analogous to the Reformation as viewed by Protestants, would have seemed to him not only to show an extraordinary ignorance of history and indifference to Tradition, but also a contempt for the Church’s ongoing Magisterium. Like Pope Benedict XVI, he believed in “the hermeneutic of continuity”.

…Deep in history, Newman understood very clearly that Councils move “in contrary declarations...perfecting, completing, supplying each other”. Vatican I’s definition of papal infallibility needed to be complemented, modified by a much larger teaching on the Church, so, Newman correctly predicted, there would be another Council which would do just that. But equally Vatican II needs complementing and modifying. Newman keenly appreciated that Councils have unintended consequences by virtue both of what they say and what they do not say. The tendency is for the former to be exaggerated, as happened in the wake of Vatican II, when one might have supposed that the Church had no other business except justice and peace, ecumenism, interreligious dialogue, and so on. But what Councils do not deal with, and therefore neglect, is also of great significance: thus Vatican II was deafeningly silent about what was to become the main preoccupation of the pontificate of John Paul II — evangelisation.

In the decades that preceded Vatican II, Newman was a source of encouragement and inspiration to those seeking the renewal of the Church. The return to the Patristic sources that characterised the Oxford Movement, of which Newman was the leader as well as its leading theologian, anticipated the great twentieth-century French ressourcement of Jean Danielou, Henri de Lubac, and Yves Congar, without which the renewal of the Second Vatican Council would hardly have been possible. In the post-conciliar time in which we are living, I believe that John Henry Newman is an invaluable guide to a true understanding of the Council, free from distortions and exaggerations, an understanding that is informed by a sense of history and the development of doctrine, as well as by an appreciation of the limitations of Councils and their relationship to each other.

end

https://www.ewtn.com/catholicism/library/father-of-vatican-ii-5699

—Ian Ker, “The Father of Vatican II,” EWTN.com, taken from L’Osservatore Romano, 22 July 2009, page 7

We can interpret Newman in the context of the two cultural movements that succeeded each other in Western Europe—Neoclassicism followed by Romanticism.

Romanticism was a reaction against Neoclassicism, which characterizes well the logic, order, and structure of Scholasticism and Trent. Trent has been described as a summary of medieval theology, and indeed it is.

Newman’s theology was a reaction against the sterile Scholasticism of his day—his ressourcement, while not exactly Romanticism, was inspired by the idea of freedom—that is, freedom from the theological strictures of the day—that marked not only Romanticism but also the Reformation and Vatican II, which has been described as the Catholic Reformation 500 years late.

Neoclassicism

“The dominant literary movement in England during the late seventeenth century and the eighteenth century, which sought to revive the artistic ideals of classical Greece and Rome. Neoclassicism was characterized by emotional restraint, order, logic, technical precision, balance, elegance of diction, an emphasis of form over content, clarity, dignity, and decorum. Its appeals were to the intellect rather than to the emotions, and it prized wit over imagination.”

Romanticism

“A movement in art and literature in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries in revolt against the Neoclassicism of the previous centuries...The German poet Friedrich Schlegel, who is given credit for first using the term romantic to describe literature, defined it as ‘literature depicting emotional matter in an imaginative form.’ This is as accurate a general definition as can be accomplished, although Victor Hugo’s phrase ‘liberalism in literature’ is also apt. Imagination, emotion, and freedom are certainly the focal points of romanticism.”

https://uh.edu/engines/romanticism/introduction.html

—Kathleen Morner and Ralph Rausch, “What is Romanticism?” NTC’s Dictionary of Literary Terms (1997)

Trent in a Nutshell

“[The Council of Trent] thus represents the official adjudication of many questions about which there had been continuing ambiguity throughout the early church and the Middle Ages. The council was highly important for its sweeping decrees on self-reform and for its dogmatic definitions that clarified virtually every doctrine contested by the Protestants.”

https://www.britannica.com/event/Council-of-Trent

—The Editors of Encyclopaedia Britannica, “Council of Trent,” Britannica.com, Updated October 6, 2022

Vatican II - What Was It All About?

“As a result of Vatican II, the Catholic Church opened its windows onto the modern world, updated the liturgy, gave a larger role to laypeople, introduced the concept of religious freedom and started a dialogue with other religions.

“...‘We really haven’t made our peace as a Catholic Church, as an institution, with the Enlightenment,’ Mickens says. ‘The Vatican is a great example. It’s an absolute monarchy. The Enlightenment got rid of all that.’”

https://www.npr.org/2012/10/11/162594956/vatican-ii-a-half-century-later-a-mixed-legacy

—Sylvia Poggioli, “Vatican II: A Half-Century Later, A Mixed Legacy,” npr.org, October 11, 2012

Romantic Influence in Newman

“Newman seems to suggest that art and literature may, in fact, be more effective than preaching and theology in transmitting important truths.

“That is exactly right. If you want to teach your students about religion, it is much better to teach them about literature that involves religion than teaching them theology. And Newman used his novels and poetry as a vehicle for his theological ideas.

“You see, Newman never wrote a summa. If you want to know about Newman’s theology of purgatory you have to go through his ‘Dream of Gerontius,’ and if you want to find out how Newman thought we should approach the secularized world, you should go through his novel ‘Callista.’ Newman says in a letter that he is sorry Catholics have not taken the novel more seriously. ‘Callista’ is far more important than Newman’s other novel, the semi-autobiographical ‘Loss and Gain.’ By the way, ‘Callista’ is also a good read; it is quite good for a romantic story.”

—Stefano Rebeggiani, “Newman key to understanding Vatican II and ecclesial movements, expert says,” Angelus News, October 10, 2019

In a word,

Newman laid the theological groundwork for the Catholic Reformation 500 years

late.

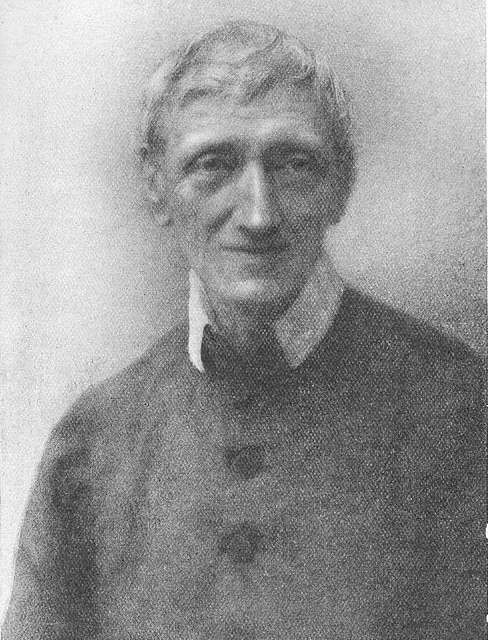

Public domain image

ReplyDeleteImage link:

https://jenikirbyhistory.getarchive.net/amp/media/jane-fortescue-seymour-portrait-drawing-of-the-very-rev-john-henry-newman-13e150

Gonzalinho

“Jane Fortescue Seymour Portrait drawing of John Henry Newman”

DeleteGonzalinho

7 CRITERIA FOR EVALUATING THE DEVELOPMENT OF DOCTRINE IN THE CHURCH

ReplyDeleteAlthough the Church does not change Her teachings, it has been recognized since at least the fifth century with Vincent of Lérins’ Commonitorium that doctrine does “develop” over time. The fullest exposition of this idea comes from Blessed John Henry Newman’s (1801-90) An Essay on the Development of Doctrine.

…Newman draws a distinction between “development” and “change,” or what he calls “corruption.” He defines an authentic development as the “germination and maturation of some truth or apparent truth on a large mental field” (1.1.5.). For example, the seed form of the doctrine of the Trinity may be seen in Scripture (“the Father and I are one” (John 10:30)), but it isn’t until the fourth century at the Council of Nicea (325) that a nuanced articulation is attempted, such that we now say that the persons of the Trinity are “consubstantial” (homoousios).

A corruption, on the other hand, is “the breaking up of life preparatory to its termination. This resolution of a body into its component parts is the stage before its dissolution; it begins when life has reached its perfection, and it is the sequel, or rather the continuation, of that process towards perfection, being at the same time the reversal and undoing of what went before” (5.3.). For example, Newman saw the fourth century Arians, who did not believe that the persons of the Trinity are consubstantial, as offering a corruption when they introduced the idea that the Logos is part of God’s creation and, as Arius famously said, “there was a time when the Logos was not,” which stands in contrast to John’s claim that “In the beginning was the Logos and the Logos was with God, and the Logos was God” (1:1).

How can we know what is a development and what is a corruption? In order to determine the difference between the two, Newman offers seven “Notes,” or litmus tests, that may be applied to any doctrine.

https://dailytheology.org/2016/09/15/theology-101-newmans-concept-of-doctrinal-development/

—Stuart Squires, Ph.D., “Theology 101: Newman’s Concept of Doctrinal Development,” Daily Theology, September 15, 2016

To be continued

Gonzalinho

Unity of Type

DeleteThe first note of genuine development Newman calls unity of type. He considered this first criterion the most important of the seven.

What he means by type is the external expression of an idea. The unity or preservation of type refers to the continual presence of a main idea despite its changing external expression. When we see change in the teaching on a subject, can we discern nevertheless that the main idea remains unchanged? If so, we know that the change is a genuine development, not a corruption.

…Continuity of Principles

The second note of genuine development is continuity of principles.

Newman insists that for a development to be faithful, it must preserve the principle with which it started. While doctrine may grow and develop, principles are permanent.

…Power of Assimilation

The third note of genuine development is power of assimilation.

In introducing this criterion, Newman notes that in the physical world living things are characterized by growth, not stagnancy, and that this growth comes about by making use of external things. For example, as human beings we grow by taking into our bodies external realities such as food, water and air.

…For Newman, a true doctrinal development is capable of assimilating external realities (such as non-Christian philosophical concepts, customs or rites) without in any way violating its principles. In fact, in the process of assimilation it’s the external realities themselves that are transformed (once they are assimilated), not the doctrine.

In Newman’s view, the more powerful, independent and vigorous the idea, the greater its power to assimilate external ideas and concepts without losing its identity.

…Logical Sequence

The fourth note of genuine development is logical sequence.

By this Newman means that a doctrine that’s defined and professed by the Church at a point historically distant from its original founding can be considered a development, and not a corruption, if it can be shown to be the logical outcome of the original teaching.

To be continued

Gonzalinho

7 CRITERIA FOR EVALUATING THE DEVELOPMENT OF DOCTRINE IN THE CHURCH

DeleteContinued 2

…Anticipation of Its Future

The fifth note of genuine development, which could be seen as a corollary of the previous one, is anticipation of its future.

Doctrines in some way imply or allude to their later development. So authentic developments will have some logical connection to the original deposit of faith, however vague the “embryonic” form might have been in the earliest days of the Church.

…Conservative Action

The sixth note of genuine development is conservative action upon its past.

In other words, a development is not a corruption if the doctrine proposed builds upon the doctrinal developments that precede it, often clarifying and strengthening them. A corrupt doctrine, on the other hand, is one that contradicts or reverses a preceding doctrinal development.

…Chronic Vigor

The seventh note of genuine development is chronic — that is, abiding — vigor.

As long as a doctrine maintains its life and vigor, its ongoing development is assured. However, once a corruption enters into the process, it leads, by its nature, to death and decay.

…When we talk with our Protestant friends about the development of doctrine, we should point out that nearly every Christian tradition accepts this reality in some form or another. For example, the Nicene Creed’s profession of the Blessed Trinity doesn’t appear explicitly in Scripture; instead, it’s a development of truths found in Scripture. Yet most Protestant denominations affirm this doctrine.

Newman’s seven criteria help us see that some kinds of doctrinal change, resulting in greater complexity, are not only legitimate but also necessary. To borrow Newman’s analogy: An acorn that somehow changed into a walnut would be a mutation. But an acorn that never developed into an oak would be lifeless.

So it is with the “acorn” of the Gospel.

https://www.simplycatholic.com/the-development-of-doctrine/

—Brendan Murphy, “The Development of Doctrine,” Simply Catholic

Gonzalinho

WHY IS NEWMAN THE “FATHER” OF VATICAN II?

ReplyDeleteWhen Newman became a Catholic in 1845, he was the most important convert to the Church since the Reformation. His Scriptural and Patristic theology was alien to a Church that was then dominated by a scholastic theology and untouched by the later Scriptural, Patristic, and Thomist revivals. It was the Second Vatican Council, of which he is often called “the Father”, that finally vindicated his theology. The late Cardinal Avery Dulles called him the most seminal Catholic theologian of the 19th century. His classic Essay on the Development of Christian Doctrine (1845), which fell under the suspicion of the two leading Roman theologians of the day, is the starting-point for modern Catholic theology of development. His On Consulting the Faithful in Matters of Doctrine (1859), which was denounced to Rome by one of the English and Welsh hierarchy, predated by more than a hundred years the Second Vatican Council’s Decree on the Apostolate of the Laity and the chapter on the laity in the Constitution on the Church. The final chapter of the latter on the Blessed Virgin Mary was the result of the Council’s decision not to have a separate document on Our Lady; its Scriptural and Patristic theology is in accord with Newman’s own Mariology in his A Letter to Pusey (1866). Newman’s interpretation of the First Vatican Council’s definition of papal infallibility in his Letter to the Duke of Norfolk (1875) was unwelcome to the extreme Ultramontanes but was vindicated in his own time in True and False Infallibility by Bishop Fessler, who had been Secretary-General of the Council, a book that received the official approval of Pope Pius IX. Newman’s famous “toast” to conscience in the same work referred to the possibility of conscientiously refusing to obey a papal order, not to the possibility of so-called conscientious dissent from papal teachings, as is often falsely alleged.

https://www.ewtn.com/catholicism/library/father-of-vatican-ii-5699

—Ian Ker, “The Father of Vatican II,” EWTN.com, taken from L’Osservatore Romano, 22 July 2009, page 7

Gonzalinho

WHY ARE NEWMAN’S IDEAS ON THE DEVELOPMENT OF DOCTRINE IMPORTANT IN VATICAN II?

ReplyDeleteNewman’s considerable influence at Vatican II is also evident in the council’s seminal “Dogmatic Constitution on Divine Revelation (Dei Verbum).” There, the council fathers teach that the great tradition “that comes from the apostles makes progress in the church, with the help of the Holy Spirit. … as the centuries go by, the church is always advancing toward the plenitude of divine truth, until eventually the words of God are fulfilled in her.” Thus did Vatican II vindicate Newman’s great work on the development of doctrine, which grew from a theological method that brought history, and indeed life itself, back into play as sources of reflection and growth in our understanding of God’s revelation.

That Newman could make this contribution to the Catholic future was due to the fact that he was neither a traditionalist, who thought the church’s self-understanding frozen in amber, nor a progressive, who believed that nothing is finally settled in the rule of faith. Rather, Newman was a reformer devoted to history who worked for reform in continuity with the great tradition, and who, in his explorations of the development of doctrine, helped the church learn to tell the difference between genuine development and rupture.

…Newman can also help us “read” the post-Vatican II situation in which the church finds itself because he knew, in the late 19th century, that trouble was brewing: “The trials that lie before us,” he preached in 1873, “are such as would appall and make dizzy even such courageous hearts as St. Athanasius, St. Gregory I, or St. Gregory VII.” Why? Because a world tone-deaf to the supernatural – which Newman saw coming – would be a world in which Catholics were seen as “the enemies … of civil liberties and of human progress.”

https://www.catholicherald.com/article/columns/newman-and-vatican-ii/

—George Weigel, “Newman and Vatican II,” The Arlington Catholic Herald, April 22, 2015

One of the most contentious questions in the reception of the documents of the Second Vatican Council is that of the relationship between unchangeable and absolute truth, on the one hand, and the human expression of that truth in a variety of historically-conditioned forms of thought, on the other. In short: Given that they did not fall from heaven, how do we maintain the enduring validity of the statements of truth asserted in confessions, creeds, and dogmas, and, yes, the documents of Vatican II, while acknowledging their historical conditioning? The answers given to this question of unchanging truth and history reflect conflicting interpretations of Vatican II and its work-product, its sixteen documents.

https://www.catholicworldreport.com/2018/10/26/history-unchanging-truth-and-vatican-ii/

—Eduardo Echeverria, “History, unchanging truth, and Vatican II,” The Catholic World Report, October 26, 2018

Gonzalinho

WHY ARE NEWMAN’S IDEAS ON SENSUS FIDELIUM IMPORTANT IN VATICAN II?

ReplyDeleteThe canonical doctrine of reception, broadly stated, asserts that for a law or rule to be an effective guide for the believing community it must be accepted by that community.

This doctrine is very ancient. It began with John Gratian in the twelfth century. Gratian based his version of the teaching on the writings of Isidore of Seville (seventh century) and Augustine of Hippo (fifth century). The development, varieties and vicissitudes of reception have been explored in recent years in a series of important studies by Luigi DeLuca, Yves Congar, Hubert Müller, Brian Tierney, Geoffrey King, Richard Potz, Peter Leisching, and Werner Krämer. This present work draws upon those historical studies and attempts to formulate the doctrine itself. This is an effort to articulate the theory of canonical reception.

Reception has been described as a spectrum of opinions about the establishment of canonical rules and their acceptance or rejection by their subjects. It has been characterized as no more than a series of explanations for failed laws. But reception is much more than a way of explaining why laws did not work. It is a sound canonical theory about rule-making which has firm footing and long standing.

The theory of reception has taken a variety of forms. One is the philosophical claim that the acceptance of law by the people is an essential part of the law-making process. Another holds that reception is simply a way of acknowledging that some laws are not very well cast and are, in fact, ineffective. Because of the range of canonical viewpoints on reception the "doctrine" sometimes appears obscure or amorphous. This present study attempts to state a clear and coherent doctrine of canonical reception.

https://arcc-catholic-rights.net/doctrine_of_reception.htm

—James A. Coriden, “The Canonical Doctrine of Reception,” Association for the Rights of Catholics in the Church, October 26, 2018

Vatican II. The council’s focus on what the Church itself was and how it related to the larger world necessarily involved a deeper appreciation of all believers in the Church. The laity in particular needed to be reminded of their inherent dignity and of their contribution to the building up of God’s kingdom. The council spoke of all the faithful participating in the offices of Christ as prophet, priest, and king. Baptism into Christ means that each believer can claim to exercise these offices. The council also spoke of the Holy Spirit imparting the gift of faith and bestowing charisms on each Christian. A positive, active, and dynamic understanding of the believer emerged. The teaching of the sensus fidelium in particular helped clarify the prophetic duty of the believer to proclaim the word of God. The laity were challenged to deepen their understanding of the faith by prayer, study, discussion, and committed action. The ambit of their intellectual penetration is not restricted solely to secular matters, though there obviously the laity have an especial contribution to make and in such matters they speak with particular authority. On matters of faith and morals, too, they are called to fulfil their prophetic task in communion with their leaders.

https://www.encyclopedia.com/religion/encyclopedias-almanacs-transcripts-and-maps/sensus-fidelium

—J. J. Burkhard, “Sensus Fidelium,” Encyclopedia.com

Gonzalinho

DOCTOR OF THE CHURCH

ReplyDeletePope Leo XIV on Thursday decided to declare St. John Henry Newman a “doctor” of the church, bestowing one of the Catholic Church’s highest honors on the deeply influential 19th century Anglican convert who remains a unifying figure among conservatives and progressives.

The Vatican said Leo confirmed the opinion of the Vatican’s saint-making office during an audience Thursday with its prefect, Cardinal Marcello Semeraro, and would make the decision official soon.

The designation is one of the most significant decisions of Leo’s young papacy and also carries deep personal meaning. Newman was strongly influenced by St. Augustine of Hippo, the inspiration of the pope's Augustinian religious order, and Leo’s namesake, Pope Leo XIII, made Newman a Catholic cardinal in 1879 after his conversion.

Newman, a theologian and poet, is admired by Catholics and Anglicans alike because he followed his conscience at great personal cost. When he defected from the Church of England to the Catholic Church in 1845, he lost friends, work and even family ties, believing the truth he was searching for could only be found in the Catholic faith.

The title of doctor is reserved for people whose writings have greatly served the universal Catholic Church. Only three-dozen people have been given the title over the course of the church’s 2,000-year history, including the 5th century St. Augustine, St. Francis de Sales and St. Teresa of Avila.

“This recognition that the writings of St. John Henry Newman are a true expression of the faith of the church is of huge encouragement to all who appreciate not only his great learning but also his heroic sanctity in following the call of God in his journey of faith, which he described as ‘heart speaking unto heart,’” said Cardinal Vincent Nichols, the archbishop of Westminster who helped spearhead the campaign.

https://share.google/Zw9BLwtS9BsunpNEd

—Nicole Winfield, “Pope to bestow one of Catholic Church's highest honors on Anglican convert John Henry Newman,” National Catholic Reporter, July 31, 2025

He was criticized for being pedantic and dull.

His ideas resonate mightily in today’s Church. He has been called the Father of Vatican II.

For me it is a happy decision and a wonderful event—Newman impressed upon the Church key ideas concerning the development of doctrine, and the doctrine of reception, both so important and critical today.

Gonzalinho

Doctor Sensus Fidelium

DeleteGonzalinho